Two skills that hold immense value in any workplace yet are only truly honed through experience are adaptability and resilience. In the fast-paced modern ecosystem, changes occur at a rate faster than the Vande Bharat. When faced with these changes, an executive can respond in two ways – either adapt to the ongoing changes and tinker or resist the changes to maintain a fixed trajectory. Like the churning of the ocean (Samudra Manthan, referred to in Hindu Texts), these skill sets work in tandem – some situations call for adaptation, while others demand resistance to change.

My first farm training experience serves as the foundational reference to this concept. While a conventional understanding is one thing, it’s the experience of navigating pressing situations that truly teaches us how to balance the two skill sets and use them effectively to ensure maximum knowledge dissemination while managing tensions.

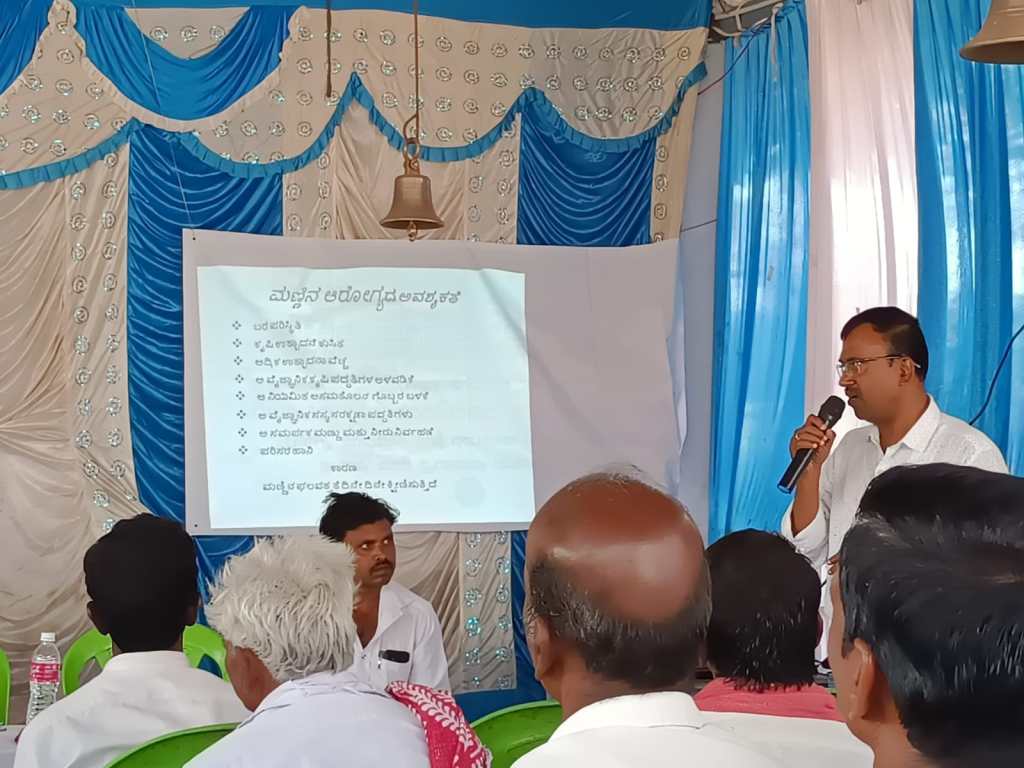

In February 2024, the first set of training sessions conducted by the JSW Foundation and Krishi Vigyan Kendra (KVK), Ballari, on Integrated Farm Systems (IFS) took place at the Ayyappa Temple in my project village of Talur, Karnataka. Amidst the training, I would also introduce my project idea, which aimed to promote horticultural intercropping as a sustainable form of integrated farming system. This project, which could be practised at a pilot level, was designed to address the challenges faced by local farmers and improve their livelihoods. With arrangements conducted and an array of eminent KVK researchers and JSW Foundation representatives awaiting the start, I was seated in the audience (initially) as an observer.

The training began with formal introductions, lighting of the ceremonial lamp, welcome addresses and songs. So far, so good. However, I felt some uncertainty bubbling through the audience. A specific nervous energy kept pulsing throughout. The audience, comprising local farmers and community members, played a crucial role in the training’s success.

The first topic of the training was concerning soil maintenance and monitoring. Conducted by Dr Ravi, the session covered the aspects of soil testing and monitoring, referencing the earth as the most fundamental tool in farming. An educational session, mostly involving knowledge dissemination, went through without disruptions. But surprisingly, there were not too many questions either.

The second topic addressed was regarding animal husbandry. Dr Ramesh KB took up this session, anecdotally calling on village history and existing practices regarding animal husbandry. With the session being slightly more interactive, questions were regularly raised from the audience. The tone, however, graduated from curious to somewhat combative. Here, I observed the first tool of adaptability, as Dr Ramesh effectively utilised humour to answer questions while parrying aside irrelevant parts. While the mood seemed better, the environment remained unsteady.

The third topic concerned bridging nutritional gaps. Dr Shilpa addressed the farmers regarding the existing dietary deficiencies in the village populace, advising them on how to bridge those gaps through any means necessary. This caused some unrest in the audience as speaking about the consumption of non-vegetarian food in a temple was construed as offensive.

The dam broke. A farmer raised his voice, discussing the continuous changes in the environment caused by the existing industrial belt, which ultimately affects crop productivity and leads to farmer losses. Accusations were thrown left and right. Tensions flared.

What would be the proper recourse? How can we get the training back on track?

Putting myself in the speaker’s shoes, I applied a technique called APR. This technique involves three steps:

- Awareness (A) – To be aware of the current situation, the stakeholders involved, the importance of the moment and the ongoing situation.

- Pause (P) – Utilise some trigger to pause any immediate reaction we wish to exhibit. For example, taking a deep breath to calm ourselves.

- Reframe (R) – Reframe the current situation, utilising specific questions to reflect and act accordingly.

Using this process, I believe the best response would be to refocus attention on the main agenda and postpone the current discussion for a future time. However, the organising team’s response was different. Dr Ramesh was resilient, firmly conveying that the topic of nutritional growth through non-vegetarian food consumption should not be considered taboo, as those who practice it remain healthy to serve family and society better. He utilised adaptability by parrying the accusations that the current situation was inevitable and that farmers would respond better by leveraging it. He mentioned several positive aspects of the current ecosystem, explaining how farmers can improve the situation and highlighting that the team was there to support them.

The crowd’s response was one of grudging acceptance. As peace was restored, I was called upon to present my ideas. My limited Kannada, being a source of easing tension, allowed me to convey my ideas effectively to the farmers.

The episode brought through a realisation that adaptability and resilience counterbalance each other. As working professionals in any field, we need to be able to leverage either one of these feelings or even both simultaneously to reach our desired goal. The art of negotiation and management is cultivated through exposure to challenging circumstances and negotiating tough situations.