Working on the field has been nothing short of an adventure—marked with moments of insight, unpredictability, and profound learning. The journey has unfolded with its fair share of twists and turns. Some days went exactly as planned—smooth sessions, open discussions, and impactful engagements. But there were just as many days when things came to a halt: communities became inaccessible, schools were closed for exams or holidays, or villages were occupied with agricultural work, festivals, or local gatherings like jatharas. These disruptions, though frequent, became part of the learning curve.

Despite these challenges, we—fellows working on menstrual health—found ways to step in, adapt, and move forward. Each visit to a school or village wasn’t just an activity, but a step deeper into understanding the people, their context, and how best to engage with them.

Activities Rooted in Dialogue and Discovery

Our sessions were designed to go beyond textbook information. They aimed to create a safe, participatory space where students could share, reflect, and learn in ways that felt personal and empowering.

Problem and Solution Tree

This activity served as an excellent tool to explore existing knowledge and concerns within the community. The tree was divided into roots, trunk, and branches:

- Roots: The foundational questions and existing beliefs about menstruation

- Trunk: The central challenges or issues faced (e.g., lack of sanitary products, myths, pain management)

- Branches: Solutions suggested by the students and strategies we could introduce together

This visual and collaborative process helped us understand what the students prioritized, what confused them, and what they wished to change. It also gave us a direct entry point to tailor the rest of our sessions around these lived concerns.

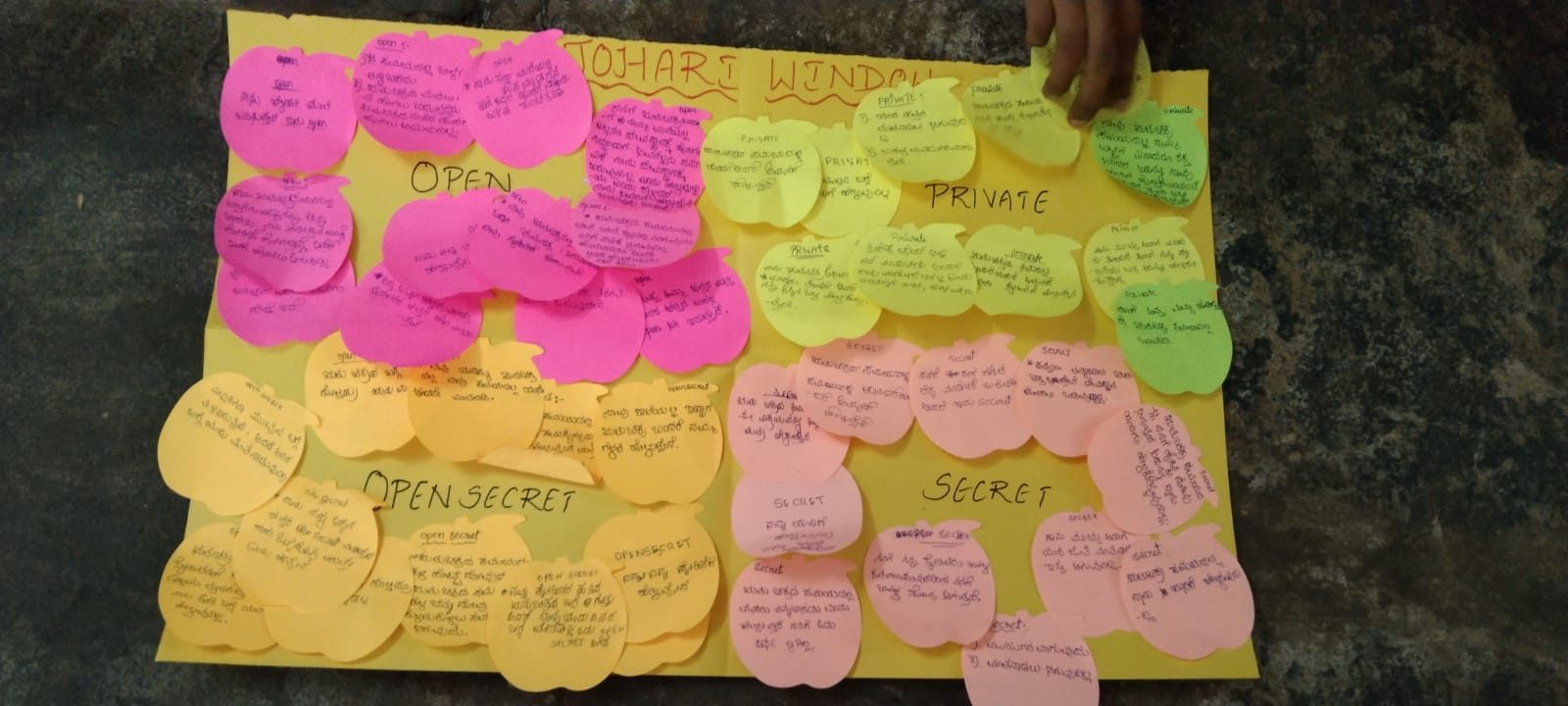

Johari Window

This activity was instrumental in gauging comfort levels and societal taboos. Students were introduced to four quadrants:

- Open: What is known and openly discussed (very minimal in most cases)

- Open Secret: Known by many but rarely acknowledged (e.g., hiding pads, feeling shame)

- Private: Known by the individual but kept hidden (e.g., pain, irregular cycles)

- Secret: Unknown to both self and others (e.g., deeper health issues)

As students filled in their windows, many confessed they had never even said the word “period” at home. This exercise laid the groundwork for more in-depth discussions and allowed girls to see they were not alone in their experiences.

From Assumptions to Listening: A Shift in Perspective

Initially, I entered the community with a plan, armed with knowledge, objectives, and timelines. But what I quickly realized was how limited my understanding truly was. The visible layers of the community only revealed a small fraction of the full picture. Most insights came from what wasn’t said—the hesitation, the body language, the whispered comments after sessions.

As I spent more time in the villages, returning to the same schools and meeting the same groups, I shifted my role from instructor to facilitator. I began giving space to their voices, letting the students and community members guide the pace and depth of our work.

With growing trust, the students began to share more—from painful cramps and concerns about irregular periods to emotional stress during menstruation. These weren’t things they had ever discussed publicly. Recognizing the gravity of these issues, I initiated the idea of a medical camp.

We collaborated with Sanjeevani Hospital to bring a gynecologist to one of the schools. This visit led to:

- On-the-spot consultations for students with menstrual disorders

- Identification of cases needing further treatment or follow-up

- Distribution of iron supplements and hygiene kits

This intervention wasn’t planned in the original project proposal. It happened because the girls finally had the space and trust to speak their truth. Their health concerns, once hidden, became actionable priorities.

Building Sustainability: Participation and Pledges

Every session emphasized 100% participation. No student was left out. Those hesitant to speak were given alternate modes of expression—drawing, writing, or group discussion. The result? A classroom environment where menstruation became a shared topic, not an individual burden.

We ended each session with a Pledge of Responsibility:

- To be a responsible menstruator

- To support peers

- To pass on the knowledge

- To end the shame

These pledges helped institutionalize the conversation. It wasn’t just a one-time session—it became a collective movement.

This journey has been humbling. I learned that education in sensitive areas like menstrual health cannot be imposed. It has to be invited. It requires patience, empathy, and the willingness to learn from those you are trying to serve.

By shifting from a mindset of “teaching” to “co-creating,” we enabled real change—in habits, in knowledge, and in dignity.

And that’s the heart of fieldwork: not just delivering a project, but building something that the community can own, carry forward, and grow beyond us.